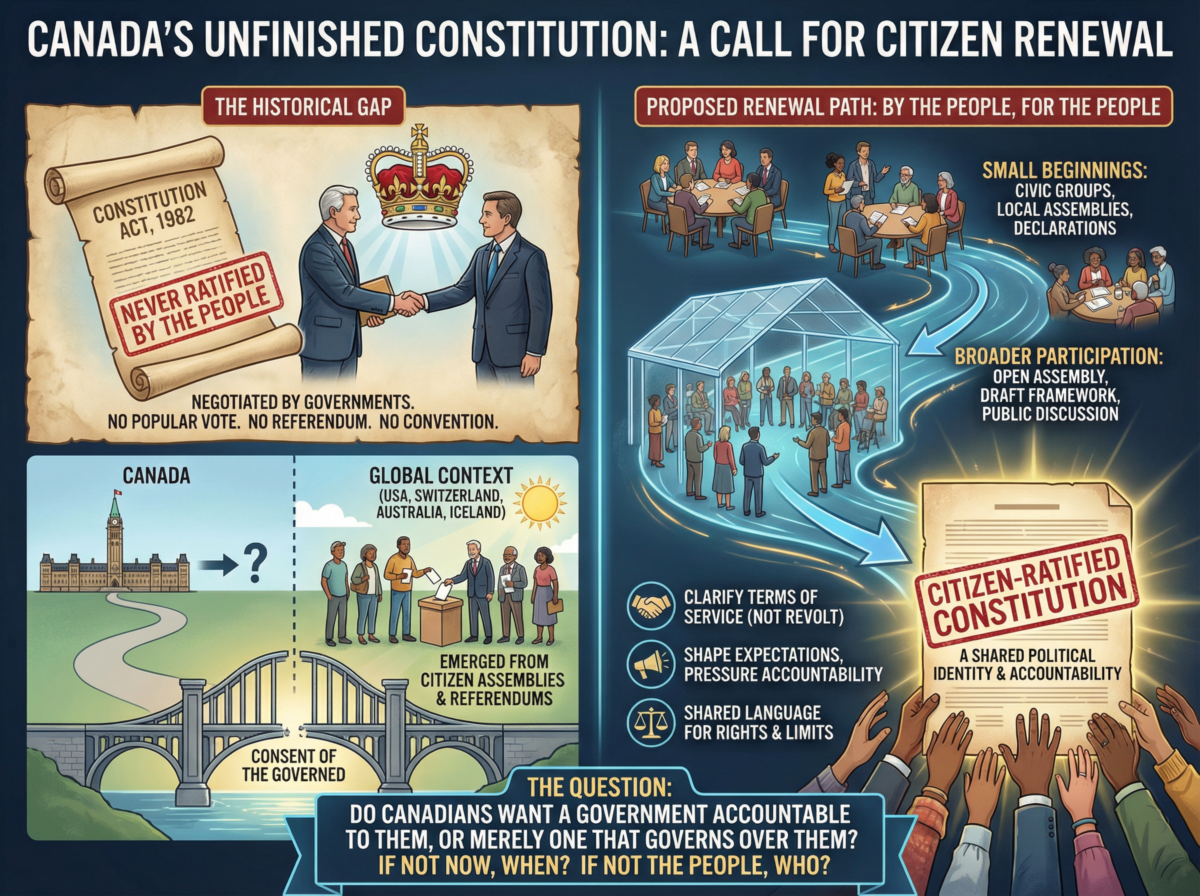

Whose Constitution Is It?

What Consent of the Governed Really Means

By Dion Klitzke

Canadians often assume they live under a constitution created by the people. Historically, that is not the case.

Unlike many nations, Canada has no constitution that was ever ratified by the people themselves. There was no national referendum, no constitutional convention of the people, and no democratic adoption. The Constitution Act, 1982—widely regarded as Canada’s foundational legal framework—was negotiated by governments and enacted without a popular vote.

This is not controversial among constitutional scholars, nor is it a fringe claim. It is simply a matter of historical record.

That reality raises a fundamental question: do Canadians want a government that is accountable to them, or merely one that governs over them?

Constitutions Define Political Identity

At a time when many Canadians feel politically fatigued, disconnected, and frustrated by a lack of accountability across institutions, this question is resurfacing—quietly but with growing urgency.

A constitution is not merely a legal document. It is a declaration of political identity. It defines who the people are, where authority originates, and what limits are placed on power.

Don’t lose touch with uncensored news! Join our mailing list today.

Countries such as the United States, Switzerland, Australia, and Iceland all went through some form of popular constitutional process. Their constitutions emerged from citizen assemblies, conventions, or referendums that clearly expressed consent of the governed.

Canada never experienced this moment.

Instead, it inherited a system rooted in parliamentary supremacy and Crown authority—structures built by governments rather than explicitly affirmed by the people. This does not mean Canada lacks legitimacy, but it does mean something important was never completed.

And what is unfinished can still be renewed.

Consent of the Governed

The idea that political allegiance is chosen rather than automatic has long-standing legal roots. Early jurisprudence in the United States addressed this question directly during its break from British rule.

Cases such as Talbot v. Janson (1795), Respublica v. Chapman (1781), and M’Ilvaine v. Coxe (1805) affirmed several key principles: allegiance to a Crown is not perpetual or inherited; political identity is formed by consent, not geography; individuals may withdraw allegiance and join a new political body; and communities of people may establish their own constitutional order.

One principle emerging from Talbot v. Janson captures this clearly: the Crown cannot compel continued allegiance where a person has chosen another political authority.

While these cases arose in the American context, the principle they reflect is universal in democratic theory: free people define themselves.

Canada recognizes this idea in theory. The Supreme Court of Canada has affirmed that popular sovereignty is a foundational principle of Canadian constitutionalism (Reference re Secession of Quebec, 1998). Yet Canadians have never been directly invited to express that sovereignty at the constitutional level.

That is the gap.

Why This Matters Now

Canada is experiencing strains that are difficult to ignore: declining trust in institutions, increasing centralization of power, unresolved federal–provincial tensions, concerns over emergency powers and surveillance, and a growing sense among Canadians that political decisions are being made without meaningful public input.

These challenges are not unique to Canada, but our constitutional framework offers no clear mechanism for the people to initiate renewal or reforms.

This has led more people to ask an unusual but reasonable question: if Canadians never ratified their constitution, could they?

From a legal and historical standpoint, the answer is YES—but only if we organize it.

Constitutional Change Starts Small

History shows that constitutions do not begin with mass participation. They begin with declarations.

In the United States, fifty-six individuals signed the Declaration of Independence. In Switzerland, seven cantons initiated the federal constitution. In Iceland, twenty-five citizens formed a constitutional council. In Estonia, roughly sixty people drafted the post-Soviet constitution. In Liberia, a committee of twelve prepared the first constitutional draft.

In every case, governments followed rather than led.

Constitutional scholars consistently note that the initial spark usually comes from civic groups, local assemblies, or committed citizens willing to articulate a shared political vision. Broader participation comes later.

This is how a people formally define who they are, what rights they claim, what powers they delegate, and what limits government must respect.

Renewal, Not Revolt

A citizen-led constitutional conversation is not rebellion. It is participation.

It does not seek to overthrow institutions, but to clarify the terms under which they serve. It does not reject Canada; it asks how Canada can be completed.

A citizens’ constitutional initiative would not replace existing law overnight. Instead, it would create a legitimate expression of public constitutional will, shape expectations, pressure governments toward accountability, and give Canadians a shared language for discussing power, rights, and limits.

This is how democratic renewal has always worked.

Imagining Constitutional Renewal

Such a process would begin modestly with a declaration of political principles, an open and transparent assembly, a draft constitutional framework rooted in democratic norms, and an invitation for public discussion.

Its value would not lie in immediate legal force, but in legitimacy. It would give Canadians something they have never had before: a constitution written with them in mind, not merely applied to them.

Canadians Should Talk About This Now

Across the world, many are re-examining the foundations of governance as states expand emergency powers and centralized control. Canada is not immune to these pressures.

Many people feel unheard, unrepresented, and disconnected from political decision-making. Yet meaningful change rarely comes from anger alone.

We do not need revolt; we need structure.

We do not need division; we need clarity.

We do not need to tear Canada down; we need to finish building it.

A Closing Invitation

Constitutional renewal does not begin in Parliament. It begins when citizens ask a simple, powerful question: who are we, politically, and by what consent are we governed?

History shows that a small group can start that conversation. Communities can carry it forward. A nation can one day embrace it.

Whether Canadians are ready is uncertain. But uncertainty has never stopped history from being made.

If not now, when?

If not the people, who?

We don’t need anyone’s permission. Canada’s future will be shaped by those willing to engage—not with anger, but with intention.

Perhaps this is the moment to begin the conversation that Canada has never fully had: a constitution written by the people, for the people, and ultimately ratified by the people.

Dion Klitzke is an independent researcher.