The Price of Freedom: A Book Review

By Sean Arthur Joyce

We can be thankful that nothing disappears without a trace. The steps of our ancestors continue to resound into the present. This is one of the realizations I had while reading Vera Maloff’s fine new book, Our Back Warmed by the Sun (Caitlin Press, 2020), in which the story of the Doukhobors in the West Kootenay is told through her own family story. Maloff’s grandfather Pete was a key figure in the Doukhobor Peace Movement—a writer, intellectual and dedicated peace activist. In these days of easy “clicktivism,” it’s easy to forget that people such as Maloff were willing to put their bodies on the line for their beliefs. Pete Maloff was repeatedly jailed for offenses as mild as leading a peace march in Nelson, BC in 1929, considered “sedition” by the authorities of the day. It was their refusal to serve in the Tsar’s army and the burning of all their weapons in Georgia that led to the wholesale immigration of the Doukhobor community to Canada in 1899. A few Doukhobors who had been imprisoned in Siberia followed in 1914. To the Sons of Freedom and other Doukhobor peace activists, this ethic extended logically to a refusal to pay taxes, on the principle that, “We are followers of Christ, therefore we cannot serve two masters. We cannot pay taxes on which firearms and ammunition are constructed.” (p. 68) For this they suffered severe repression by the Canadian government, despite being well aware of their pacifist beliefs when they entered the country.

However, some historical events leave deep, lasting grooves in the psyches of generations. Not long ago in New Denver I spoke to a woman of Doukhobor descent, a psychologist. Given her profession, I thought she would be ideally placed to write a history of the Sons of Freedom sect. But even for her these waters were too dangerous to wade into. She said the divisions caused by the Sons of Freedom remain to this day within the Doukhobor community, with a lingering bitterness many would prefer to forget. I had discussed with the psychologist the principle of epigenetics—the intergenerational transmission of trauma, a principle she was well acquainted with. Typically, studies show, the first generation—the traumatized—prefer to bury the trauma in forgetfulness, and seldom tell the story to their children. Second generations tend to inherit the psychological and physical symptoms of trauma even though they know nothing of its source. Generally it takes the third generation to finally start asking questions as to why this is occurring. Often it’s they who become the historians unearthing the story—the source of the trauma—with the goal of laying the ghosts of the past finally to rest. I wrote about this extensively in my book, Laying the Children’s Ghosts to Rest, chronicling the history of Canada’s British Home Children in the West.

Don’t lose touch with uncensored news! Join our mailing list today.

Vera Maloff, to her very great credit, treads courageously into these controversial waters. Her grandfather Pete Maloff’s steadfast commitment to pacifism caused division even within his extended family, some of whom criticized him for “abandoning” his family to fend for themselves for up to two years at a time while he was incarcerated. Others in the Doukhobor community simply viewed his crusade as a hopeless, Quixotic quest against a determined, all-powerful government. The author’s mother Elizabeth, or “Leeza,” is a major source of information for the book, although many of her memories had been suppressed for decades due to their traumatic nature. She emerges as another key figure in the story, having herself endured removal from her family to the BC Girls’ Industrial School in Vancouver in 1932 along with her siblings. Fortunately this jarring separation lasted only about a year, but in the life of a child a year can seem an eternity, and its damaging effects often last a lifetime. Having read Helen Chernoff-Freeman’s excellent book Girl #85, about her experience being interned in the New Denver residential school in the 1950s, I was shocked to learn in Maloff’s book that it wasn’t the first time the government had taken away Sons of Freedom children.

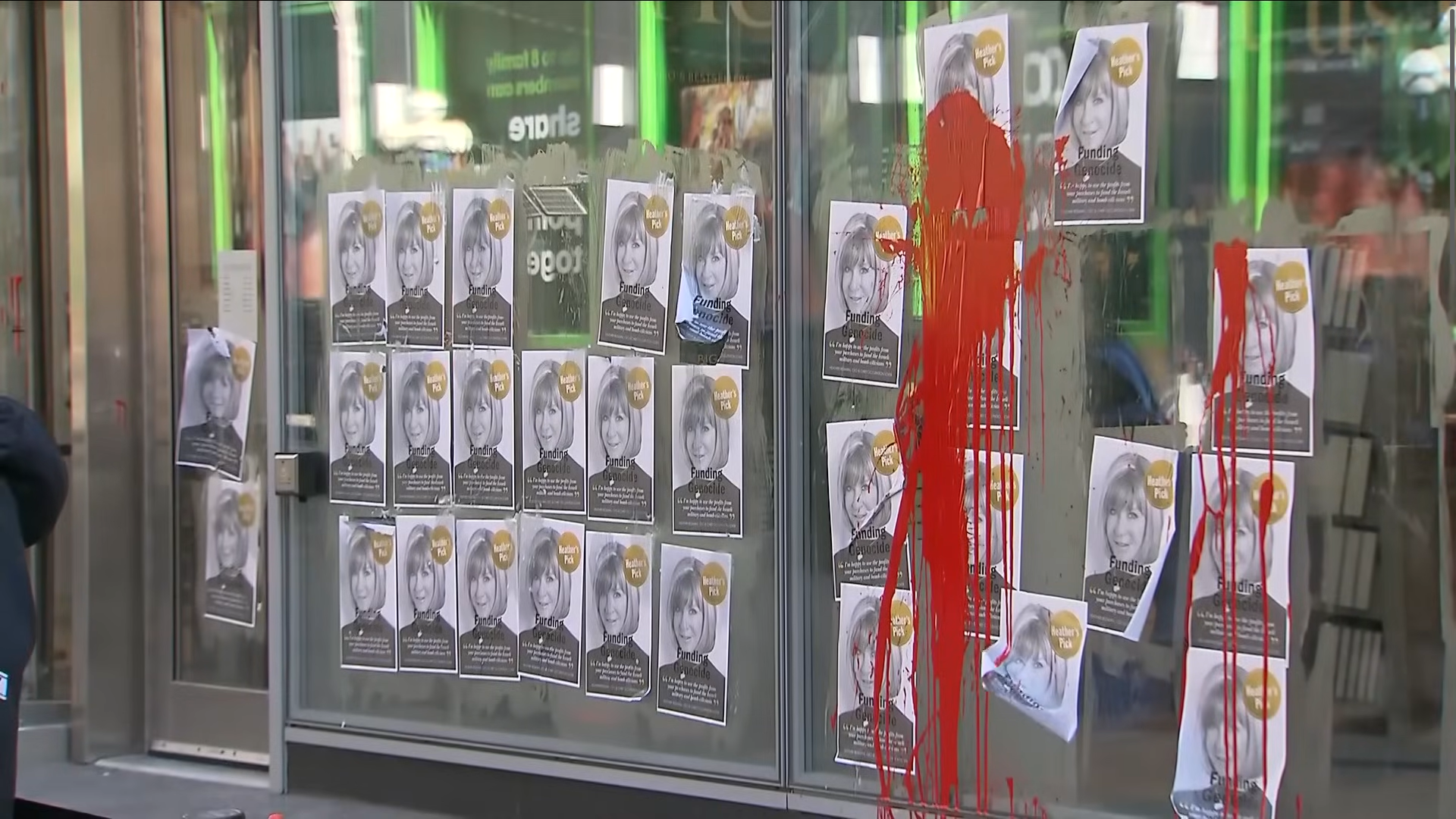

I had also not known that the logging camp known as Porto Rico south of Ymir, BC was used briefly to intern both children and parents of Sons of Freedom families, including Maloff’s mother, her three young siblings, her grandmother and great-grandmother. “At that time my grandfather Pete Maloff was imprisoned for six months hard labour in Oakalla for “obstructing a police officer” in the peaceful protest march against land taxes going to support the military.” Unsurprisingly, Pete Maloff, according to Vera’s mother Elizabeth, “was always followed,” and there were repeated attempts to infiltrate the Doukhobor community by the authorities. One such spy, Sasha Keersta, should have been an obvious one to spot, and indeed, Elizabeth’s mother (Pete’s wife) had a premonition of him in a dream. Keersta “showed up each time with a different car and driver” (p. 85) and was always nattily dressed—a major clue given the fact that it was during the Great Depression years when everyone else was walking around threadbare. A similar story of infiltration occurs in Jacques Lusseyran’s World War II memoir And There Was Light. Lusseyran’s intuition as to the true nature of people was nearly infallible; his blindness from an early age seemed to give him an extrasensory ability others lacked. The one time he didn’t trust it proved to be the time he let an infiltrator into the French underground. There’s a lesson there for today’s resistance leaders in the anti-lockdown Freedom movement.

Very much as with today’s Covid era governments passing arbitrary, unconstitutional legislation, when World War II broke out, in 1940 the Canadian government passed a military registration law—the National Registration Act—for all males 16 and over. Pete Maloff refused to register, a “crime” which was made punishable by three months imprisonment, “but Father was sentenced to several terms of three months.”As noted above, Maloff spent six months at hard labour at BC’s infamous Oakalla Prison simply for leading a pacifist protest march on Nelson’s Baker Street. (pp. 66–68) I’ve often thought that the Doukhobor community has never quite recovered from the repeated blows struck against it by the Canadian government. This is confirmed by the writing of Pete Maloff himself:

“As years went by, the Government pursued its relentless onslaught upon the Doukhobors, so that many bitter conflicts have taken place since… All these persecutions and oppressions upon the Doukhobors were presumably committed with the intention of assimilating them into the Canadian way of life. …It seems to me that this policy of assimilation, especially when done by violence, coercion and intimidation is one of the chief causes of Doukhobor unrest.” (p. 229)

In light of this, Canada’s rhetoric of “inclusion” and “diversity” rings hollow and deadly false. The “relentless onslaught” against Doukhobor communities seems to have been successful in its aim of assimilation. As with many immigrant communities, the goal now seems to be to blend in, get a good education and a good-paying career. Without a new generation of Pete Maloffs willing to put their bodies on the line for their beliefs, the continuity is broken and a great tradition all but lost. One of the great strengths of Vera Maloff’s book, however, is the realization that there’s a price to pay for such unbending idealism, with Pete’s family losing his presence for months or even years at a time. This in itself can leave emotional scars on a family. The author thus paints a nuanced picture, carefully avoiding either a condemnation of such activism nor necessarily condoning it.

The Maloff family were also actively involved in assisting Vietnam War resisters entering Canada via the Slocan Valley, at a time when mainstream society stigmatized them as “cowards,” “traitors,” or “freeloaders.” Just as with the Doukhobors, it took a great deal of moral backbone to leave one’s country and family behind—possibly forever. While others in the community stood aloof from these “hippies,” the Doukhobors generously helped them learn the skills of self-sufficiency they lacked. Most were more than willing to learn and pitch in with the workload, as the chapters on war resister Len Walker reveal. Seeing a potential protégé with shared ideals, Pete Maloff kindly took Walker under his wing.

From a writing perspective, the sole flaw I found with this book is the frequent shifts of voice from Vera as the narrator to her mother or one of her ancestors. It’s clear that even when she’s speaking in the voice of another person she’s using her skill as a storyteller to make the narrative flow seamlessly, but this can make the reader forget who is actually speaking. Late in my reading I realized the book includes a family tree which would have been helpful in sorting out who’s who and who is speaking at any given time. An index would also have been helpful, particularly for historical researchers. Still, minor flaws in a book that will earn its place as an invaluable contribution to the history of the West Kootenay.

We can be grateful that Vera Maloff has added this vital chapter to the fragmented history of the Sons of Freedom Doukhobor community. Maloff has said in interviews that she felt she needed to get her family’s stories down before her elders passed on. Her mother Elizabeth turned 100 in 2020, so her concern is justified, although the Caucasus region from which the family hails is known for some of the longest-lived people in the world. Indeed, they were studied by Soviet scientists anxious to uncover the secrets of their exceptional longevity. According to author Philip Marsden in The Spirit Wrestlers and Other Survivors of the Russian Century, who travelled the Caucasus in the 1990s after the collapse of the Soviet Union, some were rumoured to have lived to 135 or even longer.

Maloff tells me that plans are in the works to publish Pete Maloff’s sole surviving completed book, Doukhobors, Their History, Life, and Struggle. This brings me back to my opening line: We can be thankful that nothing disappears without a trace. There are many good reasons why ancestors are venerated around the world, and books such as this are just one of their invaluable legacies to us in the present. And as Vera Maloff reminds us, we must never forget the price people such as Pete Maloff paid to leave us such gifts.

ORDER Vera Maloff’s new book here: https://caitlinpress.com/our-books/our-backs-warmed-by-the-sun/

Sean Arthur Joyce is an author of poetry, Canadian history and a novel. He is better known in the West Kootenay region of British Columbia, Canada as Art Joyce for his popular newspaper columns and books on local history. www.seanarthurjoyce.ca